After thousands of conversations with women who left their law jobs in search of a truly flexible legal practice model, our curiosity got the best of us. We conducted an informal survey to find out why attorneys really left their law jobs to try to find out what their employers could have done to keep them. The results are in!

We wrote an article published in the March issue of OC Lawyer Magazine that addresses our findings specifically about why the women respondents left their law jobs. We did not find any simple solutions, but our findings may prove helpful to firms looking to improve female associate retention.

To read more, you can view the OC Lawyer article here.

Survey Results: Why are Women Really Leaving Firms? (OC Lawyer Magazine, March Issue)

We were lawyers at a fantastic law firm, and things were going well, but we quit anyway. We didn’t go to law school intending to quit. Most women go to law school intending to have long and successful legal careers, but sometimes life shifts in a way that makes a traditional law firm setting less attractive, at least for a period of time. Not only did we quit, but we essentially created a company comprised of exceptionally bright and accomplished lawyers who also happened to have quit their law firms. Since founding Montage Legal Group in 2009, we have personally spoken with thousands of women just like us. Dozens of résumés flow through our inboxes every week, primarily from women looking to continue their legal careers on significantly reduced schedules.

Women leaving law firms is nothing new, and every attorney knows at least one promising woman lawyer who quit her firm hoping to find greener grass elsewhere. Legal publications and mainstream press have been writing about women lawyers quitting law firms for over a decade, but despite law firms taking steps to retain them, women still make up a very small percentage of law firm partners. California Lawyer Magazine’s Winter 2007 cover featured the article, We’re Outta Here: Why Women Are Leaving Big Firms. The statistics have not improved since 2007 – women are still leaving law firms as much as ever. Many people assume these women quit to become stay-at-home mothers, but we have found that is not the case for the majority of women lawyers. They quit their law firms, but continue their careers, mostly within the law.

As of 2016, there is an entire segment of the legal industry essentially comprised of “law firm refugees” called “New Law” that includes virtual firms, “accordion law” companies, secondment firms, and other alternative practice models. In 2015, Joan Williams of UC Hastings Work Life Law Center published Disruptive Innovation: New Models of Legal Practice to discuss the shift to alternative legal practice models, which gained traction in mainstream media.[1] Many women who have left their law firms are joining up with these “New Law” practice models.

Many law firms have made efforts to retain women lawyers by offering reduced hour options, by forming steering committees to implement policies, by offering extended maternity leave, and by creating mentorship and other programs, but women still leave. We decided to conduct an informal survey to try to find out why women lawyers leave law firms, and also what firms can do differently to make more of them stay.[2] The results were interesting. While we did not come up with a simple solution to improve attorney retention, we did gather some relevant data to add to the ongoing conversation.

The Survey

In order to satisfy our curiosity about why we were receiving so many applications to Montage Legal from women lawyers who had already left law firms, we decided to survey our applicants and others who left their law jobs to try to understand possible causes. We surveyed close to 400 men and women who left at least one law job; 15.3% of our respondents were men and 84.7% were women. Almost every large law firm is represented within our survey population, and respondents are located all over the United States. Over 70% of our respondents graduated between 2000 and 2009. Nearly three-quarters (73%) of the survey’s respondents continue to work in the legal profession in some way. Only 17.3% of respondents became full-time stay-at-home parents. Slightly less than 10% of respondents currently work in non-legal jobs.

For purposes of this article, we focused solely on responses from the women respondents. While we hope to write additional articles digging deeper into our hundreds of pages of data, here we will discuss (1) why these women left and (2) what firms could have done to make these women stay. Please note that this is a very informal survey—we are lawyers turned entrepreneurs, and are not professional statisticians, psychologists, or researchers—and we acknowledge that this is not a scientific study.

Why Did Women Leave?

We asked respondents, “What was the primary reason you left your law firm or legal job?” Respondents were given fourteen multiple-choice options, and the percentages of women who chose a particular response are listed in Figure 1.

Results indicate that the top three reasons lawyers left included a desire to spend more time with family (18.3%), toxic work culture (18.3%), and the job demanded too much time (17.6%). Interestingly, only 1.3% of women surveyed left because of bias or discrimination.[3]

What Could Have Made Women Stay?

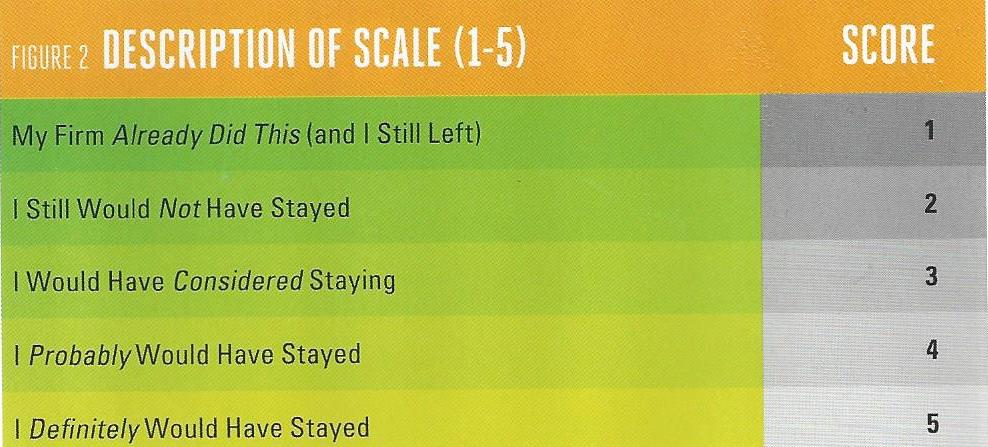

The survey asked: “What could your legal employer have done to make you stay?” Respondents were given twelve statements that identified changes a firm could have made, and were asked to rate the statement between 1 and 5, with 1s and 2s representing changes that would not have made the respondents stay, and 5s representing changes that would definitely have made them stay. See Figure 2.

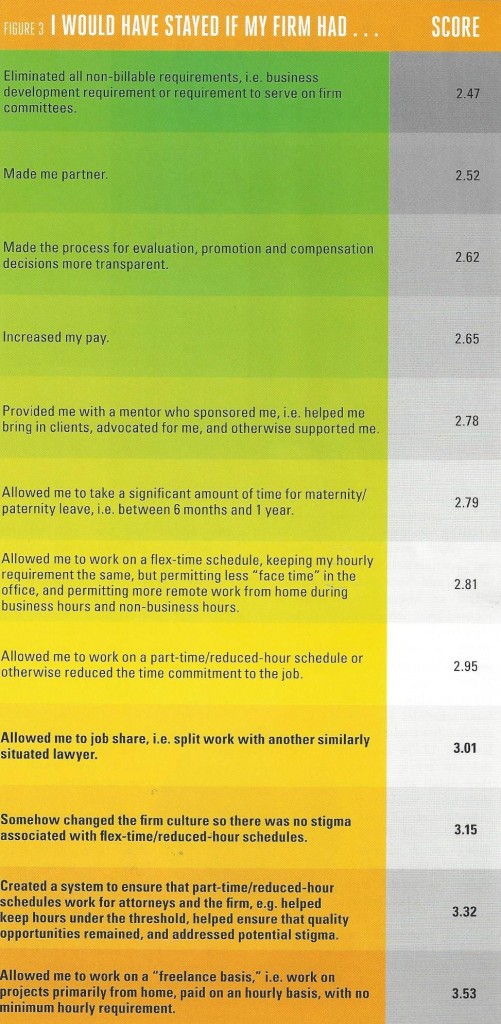

The higher the average score, the more likely the change would have affected the lawyer’s decision to remain at a particular legal job. A score under 3 leads us to believe the change would not be likely to have made the lawyer stay, and a score over 3 leads us to believe the change might positively effect a lawyer’s decision to stay. See Figure 3, summarizing the data.

The four items with scores of over 3 that seem to have the highest impact on retaining women all involve time demands: job sharing, eliminating the stigma of part-time, creating a new system to ensure that part-time schedules work, and allowing lawyers to work on hourly projects from home (freelance work). Because we surveyed those applying to become freelance attorneys and those who follow Montage Legal Group’s social media, we are very aware that our survey statistics may be skewed in favor of freelance practice.

Overall, of the women who left their firms, it appears that time was more important than money or prestigious titles, at least in the short term. Many firms have attempted to address this issue of time by offering reduced-hour schedules, or by making other accommodations to allow more schedule flexibility. Can reduced-hour schedules work, or are attorneys stuck in an unforgiving system that demands high billables and/or constant availability to clients and/or meeting court deadlines?

Can Reduced-Hour Schedules Work?

When seeking reduced hours and family-friendly options, prospective associates may seek firms with reduced-hour policies. Some law firms proudly offer reduced-hour schedules, but do they work? Or can they work? Ask many of the lawyers who have tried reduced-hour schedules, and you may receive some interesting responses.

We asked several survey questions about part-time polices and reduced-hour schedules, and this is what we learned:

- 31.2% of women respondents tried reduced-hour schedules before leaving their firms.

- 39.7% of women respondents said reduced-hour schedules were not offered at their firms.

- Of those whose firms offered reduced-hour schedules but did not try a reduced-hour schedule before leaving, 12.7% said they did not try it because they didn’t think that their hours would stay below the agreed upon threshold, and 10.7% didn’t try it because they felt there was a stigma associated with working on a reduced-hour schedule.

- Of those who tried a reduced-hour schedule, 16.9% had hours “between 85% and 100% of the normal hourly requirement” and 30.3% had hours between “between 75% and 84% of the normal hourly requirement,” meaning that almost half were still working at over 75% of their normal schedule (which may have been equivalent to a non-attorney, full-time position at 40+ working hours per week).

- Of those who tried a reduced-hour schedule, only 3.4% said their hours were reduced to 50% or less of their normal hours.

- Of those who tried a reduced-hour schedule, 59.1% said they were more content, defined as “experienced more happiness and less stress,” while working on a reduced-hour schedule than when they worked full-time.

- Only half of those who tried a reduced-hour schedule were able to keep their hours at or below the agreed upon threshold (49.4% said yes, and 50.6% said no).

- Of those who tried a reduced-hour schedule, 74.4% felt there was a stigma associated with working on a reduced-hour schedule.

What does this all mean? Contrary to widespread opinion that reduced hour schedules do not work and do not reduce stress, it appears that the majority of lawyers who tried reduced-hour schedules were happier. But as the results indicate, and as one respondent commented, “Reduced hours are nice in theory, but they’ll never work without [a] system or program to ensure that both the attorney and the firm honor the commitment . . . And there’s so much stigma, most attorneys will never say anything about how their workload is too high.”

It appears that many reduced-hour policies still need some adjustments to make them more successful. Firms with reduced-hour policies may consider addressing (1) keeping hours at the agreed upon threshold, (2) the stigma associated with reduced-hour schedules, and (3) allowing an option for a significantly reduced schedule, at 50% time or less, even if it means shifting to hourly compensation.[4]

Firms interested in retaining top talent may consider creating systems to ensure that reduced-hour policies work as planned for both attorneys and the firms. Indeed, 36.6% of those who answered said they “probably” or “definitely” would have stayed had their firms had programs to monitor the reduced-hour programs. Firms may also address the stigma that comes with working a reduced-hour schedule, starting with their leaders. Without solving the stigma problem, attorneys may be unwilling to try such programs (as our results indicate), and those who do try them will hesitate to speak up about hours creep or other failings in the program. In other words, without eliminating the negative stigma, an otherwise beneficial program may fail.

Firms have some choices to make: Is it better to retain part-time lawyers and foster firm loyalty, with the hope these would-be defectors will return to full-time and possibly even become rainmakers to benefit the firm? Or is it better for firms to let would-be part-timers go on their way, and bring in new talent to replace them? While some attorneys want to stay at a reduced-hour schedule indefinitely, there are many hundreds or thousands of others who would happily increase their hours as time progresses and life circumstances change.

What Lies Ahead?

High billing requirements and culture toxicity can be complex issues to solve. Unfortunately, we do not have all the answers, but we hope our data adds to the discussion. Some programs and solutions may help retain some women lawyers, but there is no universal solution when dealing with subjective career and life issues. Because retaining women lawyers continues to be a priority in many law firms, we hope this survey data will assist in firm’s efforts to find internal solutions to this concern.

As we enter our seventh year in an alternative practice model, we have learned from experience that when women leave or take a step back, it is typically not forever. While freelance lawyering may be a long-term choice for some, we have seen many former freelancers reenter traditional legal practice, including joining law firms and in-house departments, starting their own law firms, and even becoming administrative judges. If firms could have retained these women in some capacity, we believe that after a period of years, many of these women would still be at their firms—back to full-time work, happy, and possibly even some of the firms’ best rainmakers. While many smaller firms are grateful to have so many excellent freelance lawyers available to support their practice, we believe everyone would benefit if law firms could find ways to retain women by creating and welcoming flexible work schedules and other alternative or reduced-hour solutions leading to increased career satisfaction for women lawyers and lawyers in general.

ENDNOTES

- [1] See Parents in Law: Is it Possible to Be Both an Attorney and a Committed Mom or Dad? and Making One of the Most Brutal Jobs a Little Less Brutal, Leigh McMullan Abramson, The Atlantic (September, 2015); Don’t Leave When You Leave, Joan Williams, The Huffington Post (July 31, 2015); Disruptive Innovation – New Models of Legal Practice, Joan Williams, UC Hastings College of Law, Work-Life Balance Center.

- [2] We conducted the survey “How Can Law Firms Keep Good Lawyers” with Kate Mangan, a former BigLaw lawyer and current owner of a consulting company called Donocle, who will be authoring articles based upon our data to be published in various future publications.

- [3] We hope to conduct more research into the term “toxic work culture” as we did not define it in the survey, and it ended up being one of the top three responses.

- [4] Of the lawyers who decide to freelance with Montage Legal Group (i.e., work remotely for law firms on an hourly or project basis), most want approximately 10-20 hours per week of billable work. Compared to a 2000-hour-per-year billable requirement, that amounts to about 50% or less of a normal law firm billable requirement. Our survey shows that only 3.4% of lawyers who tried part-time were permitted to work at 50% time or less.

You must be logged in to post a comment.